I submitted this piece to Dazed magazine in March 2016. The ideas and projects described within were nascent, as was the blockchain industry. Unfortunately, the piece was rejected on the basis of being too technical. I briefly tried to publish it again sometime in 2018 but lost momentum.

It’s now been five years and two months since writing, and we’ve sailed through another hype cycle and finally, I’m following through on my 2018 ambition and publishing the text as a kind of time capsule: a blockchain moment, some first prescient seeds

Bitcoin was just the beginning.

Artists and entrepreneurs are using the blockchain, the technology that underlies cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, for projects much more diverse than digital currency. The community seethes with utopianism, much like the early days of the Internet—some suggest that we can replace governments themselves.

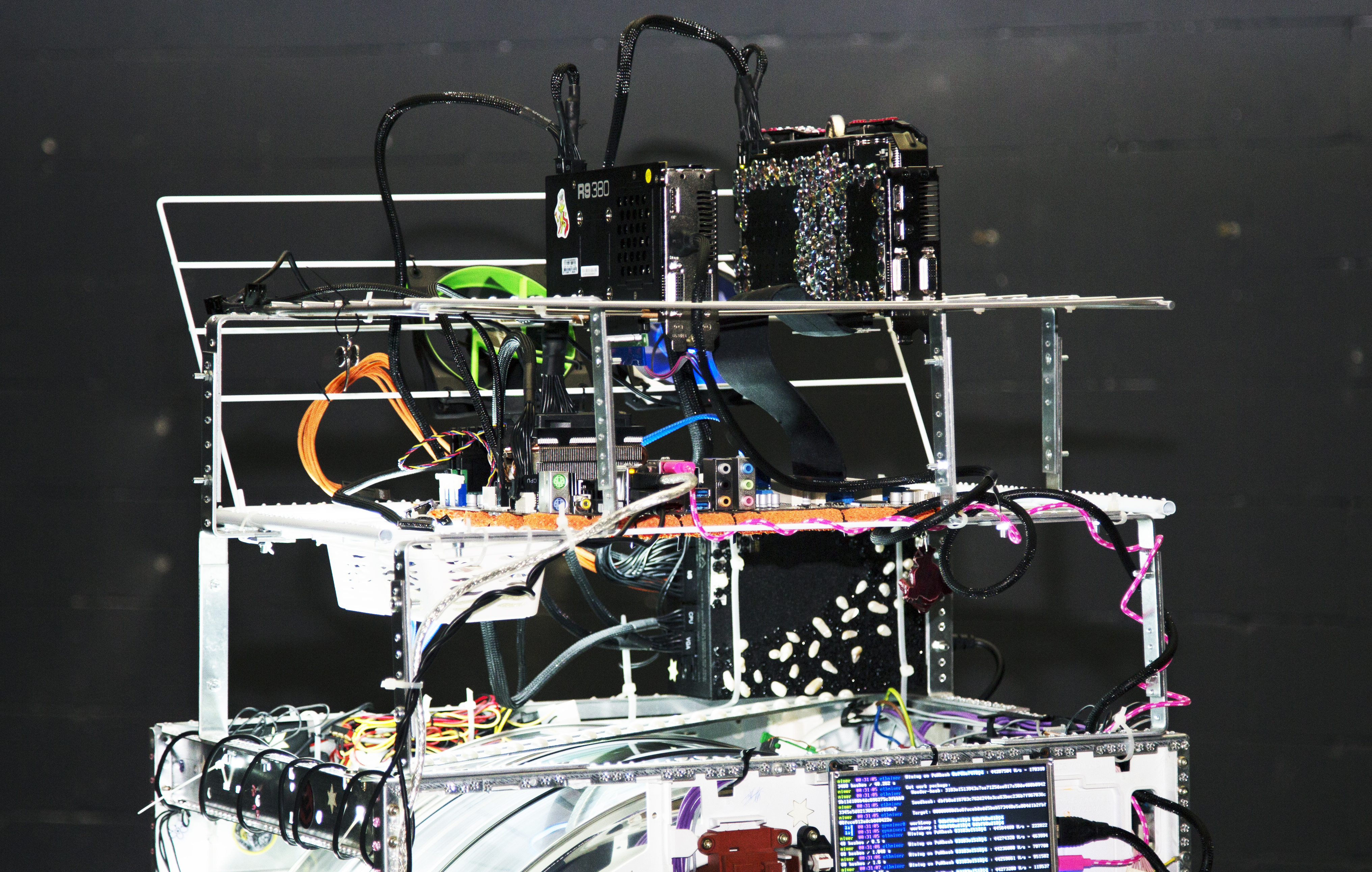

Image courtesy of PWR. Nesting Cycle (0x9ab9f7a4b85412bfbe2f4f63b1c98808851c4f32), Tongersestraat 42a, Maastricht, NL, 9/10 2015

The above tangle of wires and rhinestones is not an analog synth built by a 12 year old girl. – it’s an Ethereum mining computer, built by Swedish design and development studio PWR. This unconventional computer runs a program to “mine,” or generate, Ether—, which may sound like a fairytale substrate, but is actually a very real second-generation cryptocurrency. Instead of creating mere money, Ethereum produces tokens that can be used to power a variety of blockchain-based applications.

These blockchain-based applications run peer-to-peer, without a central organizing institution. But because of strong encryption, they make forgery or fakery nearly impossible. These qualities make them able to challenge the authority of systems – like finance or law – that are usually impenetrable to outsiders.

One such application is txtblock. Built by Rasmus Svensson and Hanna Nilsson of PWR, it is a protocol for plain text to be published on the blockchain in a permanent, but distributed, database. “The block,” they say, “is the successor of the book.” Because of the way the texts are encrypted, changing even one character will be noticed. It’s a strategy for resisting censorship, but also to question surveillance: when our every act is recorded, what does it mean to “publish”?

Another of project PWR is working on, in collaboration with Arthur Röing Baer, is a blockchain-powered collectively-owned Uber. Rasmus says, “Uber connects drivers with people who want to go someplace, but what exactly does Uber offer in the middle, except taking a cut of the money?” They’re not the only ones doing ridesharing on the blockchain – so are Arcade City in America and La’Zooz in Israel. PWR is working on trying to make sure the platform will be equitable. They describe the work as creating, “digital laws of nature that will restrict certain things and enable others.” Blockchain and cryptocurrencies always comes with the idea of a market embedded within them. Rasmus wonders, “to what extent are these neutral platforms?“

Perhaps the most ambitious blockchain application is Bitnation. It is a utopian project – audacious, unprecedented, and entirely sincere – to create a decentralized borderless nation. In Rio de Janeiro recently, Susanne Tarkowski Templehof and Alex Van de Sande launched the constitution on livestream.

Image courtesy of Bitnation.

Susanne, the founder of Bitnation, is a pirate queen if there ever was one. She first got involved with cryptocurrency in 2012 – on a Christmas eve spent at a strip club with a fellow Afghanistan war veteran and burning-man attendee. Before Bitnation, she spent 7 years as a contractor for the U.S. Government in Afghanistan, Libya, Pakistan, and Egypt, where she worked steering and stabilizing revolutions. She describes this experience as the foundation of her current work. It let her research the ways governments fail, and the reasons people become unsatisfied with them. Over time, she became convinced that the work was “immoral, and didn’t have any effect – it didn’t really matter how hard we worked. The government one-size-fits-all model was the problem.” Her father was stateless, and it’s part of what motivates her. “All my former employees from Afghanistan are now stateless refugees in Europe – it’s a really hard life,” she says.

Geographical nations, Susanne says, “are the greatest apartheid ever created.”

At the end of Bitnation’s livestream, she declares, “you may hate your government, you may think you’re born in a shit nation state – which you probably are, because most nation states are shit – and we want to demonstrate the fact that you can actually take the power of your own life and your own community and create a nation on the blockchain, and that it’s not complicated.”

So what does the future hold for Bitnation? The first set of services they are developing are notary: things like identification, marriage licenses, and incorporation. Record-keeping is ideally suited to the peer-to-peer ledger of the blockchain. They also are developing a consensus-based dispute resolution system. Eventually, they hope to offer all of the services we receive from traditional governments – including education and healthcare. But the big ask of the project is still impossible to answer. Nations, like currencies pegging their value against other currencies, derive their power from the recognition of other nations. Bitnation is currently working with the government of Estonia on an “e-registry” system, but we are still many years away from being able to travel the world with a Bitnation passport.

Image courtesy of PWR. Nesting Cycle (0x9ab9f7a4b85412bfbe2f4f63b1c98808851c4f32), Eendrachtsstraat 10, 3012 XL Rotterdam, NL, 19/12 2015

For artist Felix Kalmenson, the potential of a virtual nation state is completely different. A Jew born in the USSR, who emigrated to Israel and then to Canada – he has experienced the nonsensical violence of international conflict. He’s trying to travel back to Russia soon, but since he was born before the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s surprisingly difficult. The country that issued his birth certificate doesn’t exist anymore.

During an upcoming residency, Felix plans to begin work on a virtual Jewish state, with the goal of challenging Israel’s monopoly on Jewish statehood. His goal is to decouple Jewishness from geographical states. The idea is not without potential pitfalls, and he worries any digital state will have barriers to entry that leave out the most disenfranchised. He hopes, more than creating replacement nations, that we can use them to shift the conversation. “If you make the whole idea of state-based citizenship absurd,” he says, “we can start having a conversation about how can we extend rights not just based on citizenship, but based on our existence as humans.” Human rights like access to healthcare and drinking water should not be based on citizenship – as it is in our current system.

In Citizenfour, Edward Snowden says, “I remember what the internet was like before it was being watched, and there’s never been anything in the history of man that’s like it.” Rasmus, of PWR, agrees, “We came of age in the mid-nineties, when there was a lot of potential and visions for the internet. Cyberspace. It was supposed to be endless freedom.” Before most people understood the internet, and before many had accessed it, cyberspace catalyzed utopian visions. In the years since, it has been overtaken by social media conglomerates and government surveillance programs. The internet has changed the world, but not in the ways we hoped. Dreams die by becoming real.

Blockchain, in 2016, dwells in this same place of mesmerizing tension. It’s only 8 years old.